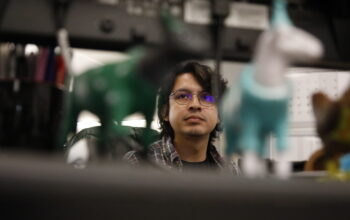

Hair as black as raven feathers, arms tattooed with skulls and facial piercings to match, Justin Emord emits the typical rocker appearance which alludes to his music career.

The 30-year-old has played in diverse venues, from the Anaheim Convention Center to outdoor music festivals, to the Whisky a Go Go in Hollywood. But when he travelled to Washington D.C. in February, Emord found himself playing a different role, advocating for music education with an envoy of representatives from the National Association for Music Merchants (NAMM).

“We were there supporting music education both at the state and federal level,” Emord said. “We were there to support specifically Title IV in the Every Student Succeeds Act because the president had zeroed it out in his budget, which came out when we were in D.C.”

NAMM is a trade organization for music products, featuring companies from different areas of the industry such as pro audio, dee-jaying, brass and woodwind, to guitars and amps for mainstream music.

The group has a foundation attached to the trade organization that supports music education programs in schools by working with the government to make sure that there is funding or funds are maintained within school systems.

According to Emord, NAMM sends members of its foundation every year to advocate and help define the language in bills to maintain support for music education throughout the country, but this time was different when President Donald Trump announced his proposed fiscal budget for the following year.

Emord said that his group was in the Newseum and were preparing to go into the Capitol the next day to work with the government and elected official, when the budget was actually proposed.

“Wow…it was heavy,” Emord said. “To find out something like that when you are supposed to go fight and support music education, and to find out that your president basically killed it. It was overwhelming, but made the task more important and a lot more serious.”

According to Emord, when they met with officials, they were all saying that Trump’s budget was dead on arrival, and that there would be a lot of negotiations between all parties involved to make sure that they agreed on a budget.

“Within 24 hours of the budget coming out, we were there fighting back, which was incredible,” Emord said. “But with Every Student Succeeds, it was authorized funding at one point for $1.65 billion for the country. Trump decided to remove the funding fully from the budget.”

Emord said that no one agreed with the proposed budget, which helped calm the group.

When discussions began with government officials, his group had an easier task than others members of NAMM from different states, because California officials understood the impact of music education.

“There’s a lot of stuff coming down the pipeline for California. That is really exciting, we were able to get the ball rolling early on,” Emord said.

Emord was a communications major in college and took a lot of rhetoric classes. At Pierce, he took a lot of business finance courses, which helps in the music industry.

“When I was going here and CSUN, never in my wildest or weirdest dreams would I have ever seen myself speaking at Capitol Hill,” Emord said.

The knowledge and familiar background that he obtained in communication and philosophy provided him the tools to communicate effectively, he said.

“To be able to use that stuff in a classroom and apply it to the real world in such an important arena like the nation’s Capitol, is priceless,” Emord said. “They set me up incredibly well to be able to go into a situation like this and succeed.”

Chalise Zolezzi, the director of public relations for NAMM, is in charge of the organization’s social media, highlighting and sharing news with various media outlets, among other responsibilities.

“NAMM is working to make the world a better place by providing passionate defenders of children to raise their voices,” Zolezzi said.

Zolezzi said the work they do at the state level and national level is important because of the impact music has on children and the community.

“Transformative experiences to see the work you are doing affects the community,” Zolezzi said. “It is to encourage everybody to make music.”

According to Emord, the foundation provides donations and has its members volunteer at schools across the nation that need support for a thriving music program.

Such was the case when the organization donated $5000 to an inner city school in D.C. to help with its lacking music program. More than 30 percent of the instruments the school had were beyond repair, and the students couldn’t use them, Emord said.

“It was eye opening to go to a school like that and see what the world is like, becuase in Los Angeles, we don’t have that problem,” Emord said. “We have schools that are hurting, but not to the extent that this school was.”

Director of Communications and Public Information for the Anaheim Elementary School District Keith Sterling said the district had a partnership with NAMM for a few years and it has helped them with their program.

“It brought back the music program,” Sterling said. “NAMM has helped guide us and develop the music program at our school districts. They donated $10,000 collectively for two years.”

NAMM hosts its annual conference in the Anaheim Convention Center and coordinates time to participate for a NAMM Day where professional musicians visit schools.

“Music is new to the students who come from underprivileged areas, but when you see them react to music, it’s powerful,” Sterling said.

Emord said that he is motivated to advocate for music education for students because he was a product of the music program at his school.

“I see the life that I’ve lived because there was a fork that I didn’t know existed, because I wasn’t exposed to music and when I was. I found this line,” Emord said.

In his career, Emord performed at music festivals for bands and artists, such as The Doors, Marilyn Manson and The Offspring. One of his basses is on display at the Hard Rock Cafe in Universal Studios.

“I owe everything in my career to music education,” Emord said. “First, to give me the tools and knowledge of music. Then NAMM, for having a convention for an artist, like myself, to be able to go in as a teenager and be able to make something out of myself by hustling, networking, and making it happen.”