Thirteen years ago, many watched over breakfast with their collective mouths agape as four loaded commercial jetliners were buried into three iconic American buildings and into a Pennsylvania field.

At the time, the nation reached for a reason. Some found answers immediately, while it took time for others. The rest may finally find their answers as visitors to the National September 11 Memorial & Museum, which recently opened in New York City.

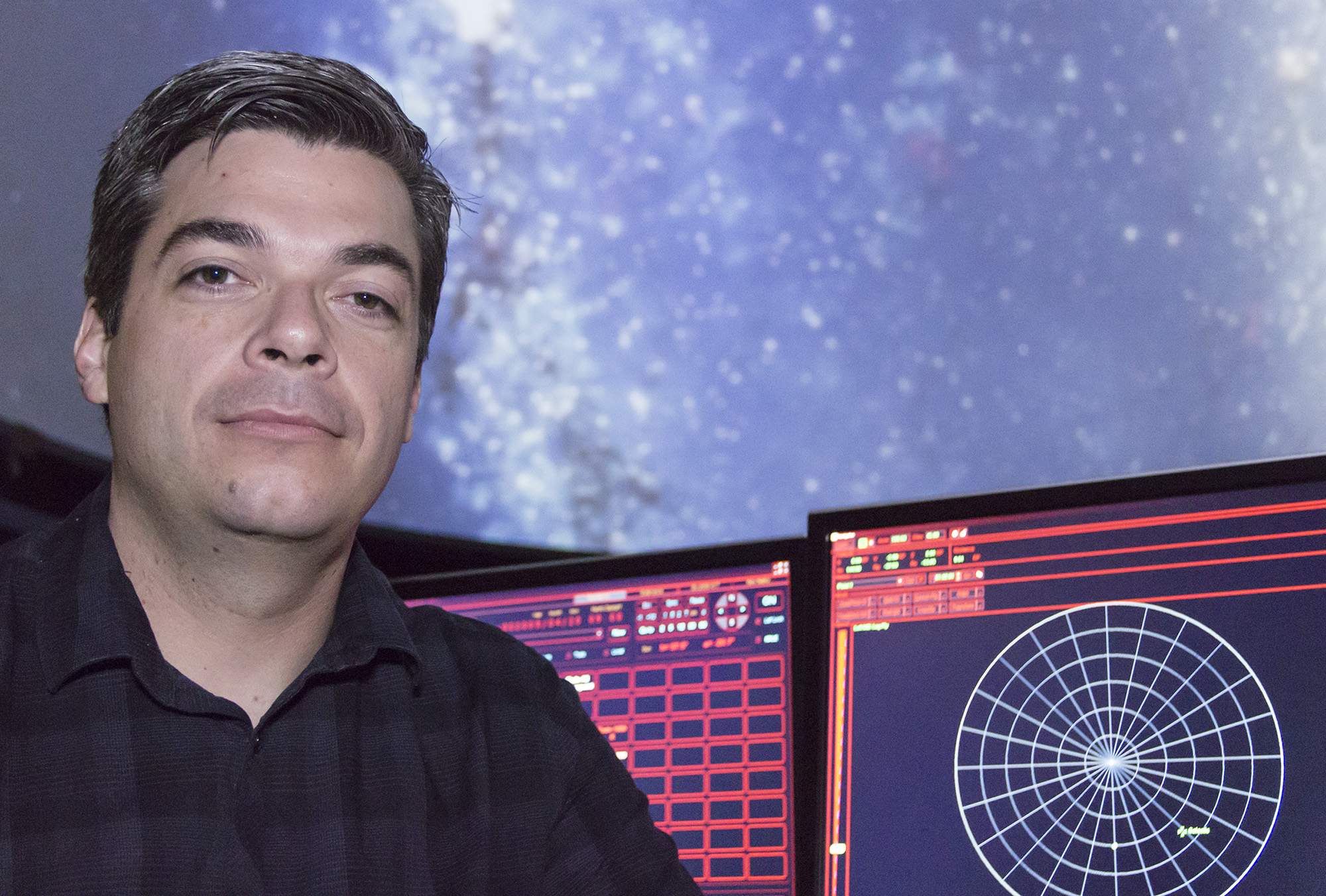

“When 9/11 happened, that really changed everything for me,” said Eric McKenny, an introspective and soft-spoken adjunct instructor of physics and planetary sciences at Pierce College.

“I was in my undergrad program in physics. I walked into the lounge of the dorm room and was seeing footage of buildings collapsing,” he said. “Everybody was in a somber mood and they were putting the flag at half-mast. I was in disbelief.”

McKenny applied scientific reasoning to help him deal with the tragedy that was gripping the country.

“A lot of people found faith at that time and I was one of the few people actually going the opposite way,” he said. “I was asking people a lot of Socratic questions about what they believe and why.”

His watershed moment did not come lightly since he was a member of a Christian church at the time.

“They’re called the Church of the Nazarene in San Ramon, California,” he said. “They’re missionaries by trade so they’re very good at dealing with people and treating you like a you’re a rock star as soon as you walk through the doors and that was very compelling to me.”

As a self-described “California brat,” McKenny’s education has skimmed the coast from the top of the state to the bottom; elementary education in Reseda, high schools in Sacramento and the Bay Area and colleges in San Diego where he attended San Diego State University (SDSU) and Point Loma Nazarene University (PLNU).

PLNU is a small private university founded in 1902 that serves a faith-based education to about 3,500 students on three campuses, according to their website.

“It was more a gradual coming out of the closet kind of thing. I was very angry at the time – very disillusioned. I think people knew before I, myself, knew,” he said. “A lot of the conservative elements at my school were of course very eager to bring me back in to the fold.”

McKenny said he was about to complete his science degree, but only after he became a non-believer did he have a “real thrill” for learning science.

“Before that it was a bunch of unrelated facts,” he said. “I never really appreciated the amount of structure that went into everything. That’s the real big, intangible benefit.”

Opinions vary on what’s an appropriate response to such tremendous grief and the questions it begs.

Charles W. Smith attended PLNU in San Diego and earned a doctorate from Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena. He has been pastor of New Life Church of the Nazarene in Northridge for more than 13 years. Smith said from the Methodist movement, Nazarenes emerged around 1908.

“The problem is that we don’t live in a perfect world. We live in one where there is sin, there is evil that takes place. I’m sure that terrorism is one thing that has really affected everybody,” Smith said. “It’s not a country necessarily that we are struggling against but an ideology.”

There could have been personal reasons in addition to the events of Sept. 11 that contributed to McKenny’s crisis of faith, Smith said.

Niaz Khani, Psy.D., is a clinical psychologist at the Pierce College Student Health Center who counsels on grief and trauma among other things.

“When people are in crisis or desperately seeking some type of support and it’s not answered that’s the time they usually lose faith in a higher being. It is very common. I see that all the time,” Khani said.

According to the 2010 U.S. Census, “non-believers” grew at a rate of nearly 16 percent while Christian expanded by little over one percent 2001 – 2008, comparatively.

Sam Marquez is a member of the Hare Krishna Cultural Center in Los Angeles who passes out copies of Bhagavad Gita from the free speech square on campus to interested students.

“In Germany during World War two they were praying, ‘Please let my husbands, my sons come back.’ But they didn’t come back,” Marquez said. “[Then they said], ‘Oh I give up my faith. What is the use.’ We cannot demand [of] God. You’re ordering him like an ATM – gimme, gimme, gimme – I want this then I believe in you. That sounds very weak.”

McKenny said there was cognitive dissonance and that people around him were more compelled with how to judge the events that happened and how to attribute sin to their daily lives rather than compassion for the people who were still grieving and suffering in New York.

“[9/11] was a shock – a fundamental shock in the way I viewed the world around me and the people I was with and how they thought. I didn’t realize until that time how much of a capacity we have to deceive ourselves,” he said.

Henry Baker is a 20-year-old computer science major. He was in third grade when he saw people falling from the twin towers of the World Trade Center on his classroom TV.

“We were doing a project. The teacher had the TV on. It said, ‘Breaking news – The Twin Towers’ and I said, ‘Whoa. What happened?’,” he said. “It didn’t affect me then … When it really affected me was when I saw it in middle school. Whoa, that really happened.”

Baker said he suffered no trauma from 9/11 and his understanding of why it happened has grown.

“I think [the Muslim hijackers] did it for the love of their religion. If they fight for what they believe in that they would go to heaven,” he said. “If it has to come to a point where [Christians] have to die for our god then we’ll do it.”

McKenny said change of beliefs is stressful, especially when it is sudden. People feel betrayed by a whole group or congregation or whoever they are with they can feel abandoned for whatever reason.

“When I [joined] atheist groups, there were a lot of people who were very angry. I found the same dogmas, so it got me to rethink my own philosophy,” he said. “I’ve a rational skeptical view overall. I’m a big fan of evidence. I guess I would classify myself as a Humanist.”

The American Humanist Association defines Humanism as a “progressive lifestance that, without supernaturalism, affirms our ability and responsibility to lead meaningful, ethical lives capable of adding to the greater good of humanity.”

Smith said that while Nazarenes come from a Christian world view, he also believes that Atheists can also lead a good life.

“Stop focusing on groups and figures of adoration and start thinking about people and their accomplishments,” McKenny said.