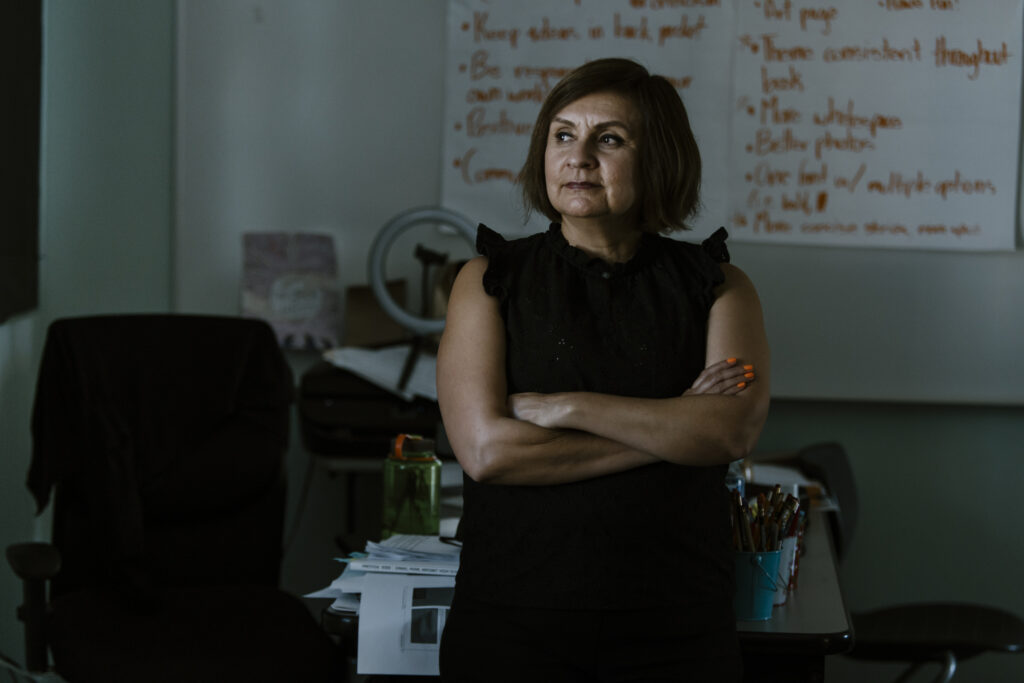

Bold, supportive—a few words that best describe the way former students felt when they spoke of their high school teacher Adriana Chavira.

But she didn’t always feel that way about herself.

Chavira’s experiences as a student journalist in high school was one of the many reasons that led to her breaking out of her timid shell.

“I’m very shy, and so just having to force my way to get out of that, out of my comfort zone while doing interviews, definitely helped me as well,” Chavira recalled.

Today, Chavira is a journalism teacher at Daniel Pearl Magnet High School in the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD). In September, the district almost suspended her when she refused to censor an article her students wrote about faculty and staff who didn’t comply with LAUSD’s COVID-19 vaccine mandate.

Sitting for an interview at a local coffee shop on a quiet Wednesday afternoon, beverage in hand, she begins to recount moments in her life that led up to the present.

An LA native, Chavira spent her childhood with LAUSD, moving from Hollywood to the San Fernando Valley, where she graduated from John H. Francis Polytechnic High School. She went to school at the California State University, Northridge (CSUN) and graduated with a Bachelor’s degree in Journalism and a minor in Chicano Studies. Chavira would later go on to continue her education again at CSUN, where she received her Master’s degree in English. All the while being a part of her school newspaper and working at a movie theater.

The journalist spirit has been with Chavira since childhood. Her household was a constant flow of news and politics thanks to her father, who would bring home a daily copy of the LA-based Spanish newspaper La Opinión.

“My sister and I learned to read Spanish using La Opinión. We learned how to read and write from that, we’d always watch the 4 o’clock news on Channel 7, then the 6 o’clock news on Channel 34,” Chavira said. “Staying up-to-date with the news and the impact it had was always big in my household since I was in elementary school and so from that, I just kind of got interested.”

As a reporter, Chavira worked for the Whittier Daily News, Inland Valley Daily Bulletin, the Desert Sun in Palm Springs and the Press-Enterprise in Riverside.

Chavira mentioned she enjoys features about people and shared a story about meeting her literary idol.

“I covered an event with Chilean writer Isabel Allende,” Chavira said. “Early on in my career, I covered a lot of Latino issues or Latino events and that kind of stuff because I was often the only person of color in the newsroom or bilingual person as well, and so there was an event where she was speaking at a luncheon for one of the school districts in the Whittier area. That was a great opportunity, just to see someone that I really admired.”

Chavira also covered news about city government which she called “very dry” and has experience with police reporting which according to her, “is a good way to hone your reporting and writing skills.”

Chavira’s LA roots however, were calling her back home.

“My career was kind of at a standstill I guess for lack of a better word, and I missed being in LA and I wanted to come back to LA,” Chavira said. “At that time, I didn’t see myself getting into the Los Angeles Times or being hired by them, and I just decided to… I was kind of unhappy with journalism for a variety of reasons, and so I just decided to switch careers.”

At the time, LAUSD started a program for people looking to switch careers, Chavira said. She joined the six-week training “bootcamp” program, as she put it, on how to teach and how to deliver lessons. After passing the program, Chavira was hired at Garfield High School in East LA to teach English and spent five years there before moving to Birmingham High School, and ultimately joining Daniel Pearl Magnet School where she has been for the past 14 years.

In a typical intro to journalism class, Chavira teaches her students ethics and the value of the First Amendment, as well as teaching them to write many different styles of articles and photography. In the advanced classes, the students are put in charge of putting together the school yearbook, news magazine, news website, and social media. She hopes that her students learn the value of keeping up with the news as well as the importance of media literacy and writing accuracy.

For Chavira, the constant bombardment of news from social media is why she stresses to her students the importance of being informed.

“All of those messages can also easily be manipulated. You often see people sharing misinformation,” Chavira said. “As well as learning about journalism, they also need to know how to verify facts, how to make sure that something is true, and also when someone tells them something, when they’re interviewing, how to verify facts as well. That’s definitely very important. And you know, kind of question everything as well. Don’t just take everything at face value.”

All throughout her entire career as a journalist, Chavira has never had an article face the chopping block for any reason. All that changed in Nov. 2021.

The Pearl Post, a student-run newspaper at Daniel Pearl Magnet High School which Chavira advises, published an article about the district-wide mandate that required all faculty and staff to be vaccinated against COVID-19 or work remotely and not be allowed on campus. The Post named the teacher-librarian and wrote about the effects of the mandate. They corresponded with the affected individual to conduct an interview but was never granted one, according to Chavira.

“They got a published article and then about a month later, I got an email from her asking that her name be removed,” Chavira said. “She cited HIPAA law, saying we were violating it.”

There was never any request to remove the whole article, Chavira said. “But even just a removal of some information is still censorship.”

For Nathalie Miranda, the reporter who wrote the article, the rest of the school year was stuck in limbo, leaving the Post to wonder what was going to happen next.

“Before the threat of suspension came, Ms. Chavira made it very clear that it was up to me and the other editors to decide what to do,” Miranda said. “She wanted to leave the decision completely up to us but then when the threat of her getting suspended came up, it kind of felt unfair to make that decision for her.”

According to Miranda, Chavira told her and the editors she was not worried about suspension and ready to face the consequences.

“I grew a new kind of respect for her after that. She was just so prepared to defend her students to the end, and I loved that so much,” Miranda said.

For Chavira, this issue began in Dec. 2021 and ended when the district rescinded her suspension.

Chavira hopes for more awareness of student journalism rights from LAUSD, adding that the district was in violation of California Education Code Section 48907 which, “specifically protects student advisors from retaliation, firing, suspension, whatever, because of something that their students wrote.”

Receiving a suspension at a school that bears the name of a deceased journalist is also ironic, according to Chavira.

“This is not something that I ever thought would happen in my school,” Chavira said.

For Stanford University sophomore and former Editor-in-Chief of the Pearl Post Itzel Luna, the way Chavira and Post staff members handled themselves made her proud.

“It once again shows how important it is for student journalists to do this work and to not back down in cases where administration is trying to shut you down and trying to get you to do something,” Luna said. “In a broader sense, it really shows that student journalism is incredibly important, and a really good reminder that it’s really important to stand up for your rights.”

When asked if the Pearl Post was affected by the censorship issue, Chavira said that hasn’t stopped them from reporting the truth.

“It gave the student editors a sense of empowerment through this. It made them appreciate journalism, appreciate the First Amendment and appreciate their press freedom rights as well,” Chavira said.